Which Fruit Trees Grow Best In The Desert?

I get this question frequently so I figured I would address this here. Any stone fruits do wonderfully here, and that includes peaches, nectarines, plums, apricots, any combo fruit like Pluot, Plerry, Aprium, etc., pomegranates, and cherries. Apples and pears do well, but are susceptible to fireblight (especially pears) and I frequently see people have that problem and need to remove them. This susceptibility can be managed to successfully grow these fruit if desired.

Other options that do well in the high desert are: almonds, pecans, walnuts, mulberries, jujubes, persimmons, olives, pineapple guava, quince,

Borderline options include: loquat, cold hardy varieties of lemon/mandarin/avocado/banana, and figs. These fall under the category of “This can grow here, but may need specific microclimates and/or cold protection during winter.” Figs are an odd addition to this list as they are almost always listed as hardy in zones 8 and 9, but frequently take cold damage and die over winter.

This page is still under construction and will continue to add additional useful information.

Menu

Fruit Tree Pollination

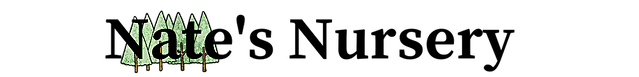

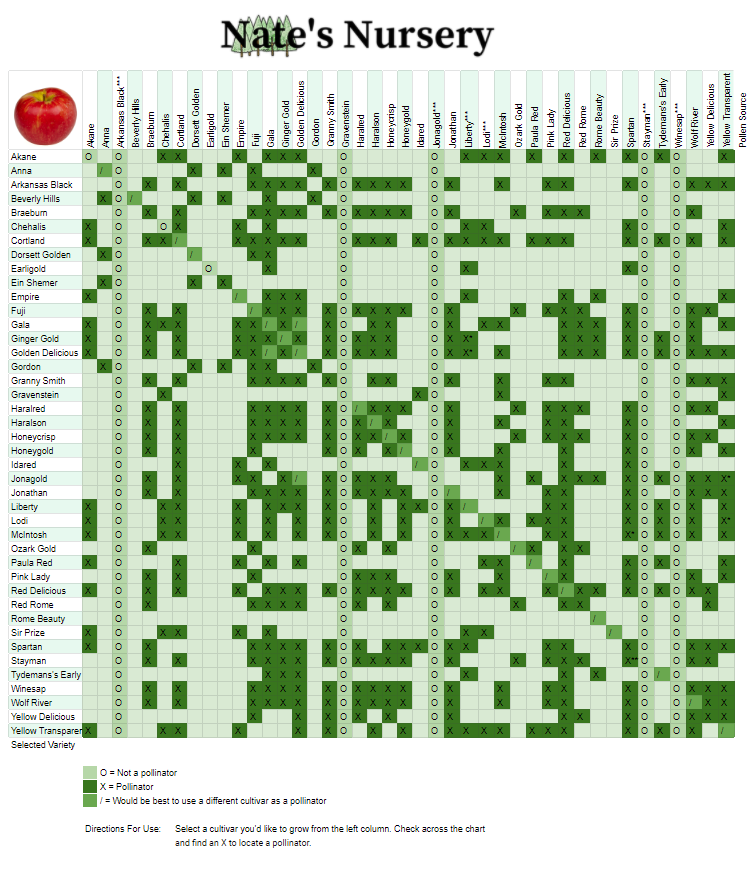

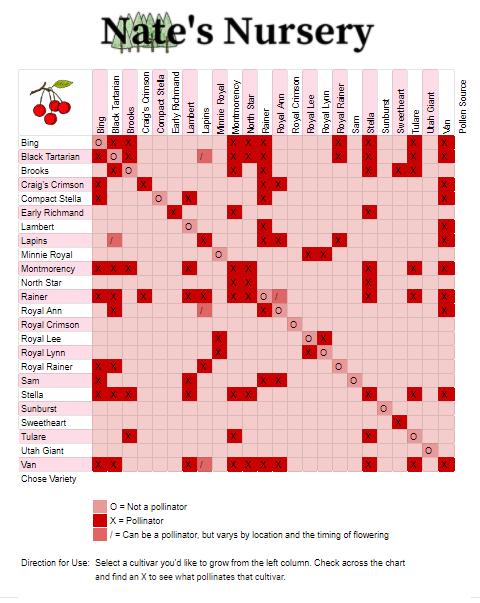

When talking about fruit tree pollination, the only constant rule is that there is always an exception. Things can change or behave differently based on location, climate, cultivars and even act differently in different years. Due to these variables, the information presented may not be 100% correct for all situations.

Pomegranates, quince, and sour cherries are self fruitful and need no pollinators. Most peaches, nectarines, apricots, citrus, and figs are self fruitful with a few exceptions (which should be explicitly stated on the tag or advertisement), and some apples, pears, Asian pears, blueberries, and plums are self fruitful. Below you can use the tables to find pollinators or to see which varieties are self fruitful.

Fruit Tree Size

There are 3 different sizes that fruit trees typically come in, dwarf, semi-dwarf, and standard. This is determined by the rootstock that the cultivar of fruit tree is grafted onto. There is usually a tag at or near the bottom that will have the rootstock listed and hopefully have care instructions.

Dwarf trees are for small spaces and can be placed with 8′ spacing. The advantage to these trees is that they stay small and are easy to prune and harvest. The fruit is a normal size, but the overall yield and lifespan of dwarf trees is reduced. Disadvantages are that dwarf trees tend to be shallow rooted which can lead to the tree uprooting or being blown over and lack of drought tolerance.

Semi-dwarf trees are medium-sized and are recommended to plant with 10′-15′ spacing. Unpruned, a semi-dwarf tree will grow up to 10′-16′ when mature. These trees are typically preferred due to their significant yield with a manageable size combined with pruning. Occasionally trees will take a year off from producing fruit if it has had a heavy crop the previous year.

Standard trees are large trees that will require regular pruning (twice a year) to keep them smaller in order to harvest, net, thin, and spray. They can grow up to 25′ or taller if left unpruned.

Pruning fruit trees is necessary to maximize fruit production. Pruning regularly can maintain the tree at a smaller size without requiring a dwarf rootstock. Due to this I strongly recommend picking a fruit tree based on a rootstock that will thrive in your soil, not necessarily based on the ultimate size of the tree if left unpruned.

Pruning Fruit Trees

Pruning a fruit tree is much different than pruning a shade or ornamental tree. The reasons for pruning are to: maintain height for ease of harvesting, raise the height of the lowest branches to allow passage underneath, increase fruit yields, control the direction of growth for the fruit tree, form strong branches that will not break under the weight of fruit, remove dead and diseased branches, and to prevent or control pests.

Pruning fruit trees is necessary to obtain a consistently large yield year after year regardless of the size of the tree/rootstock. It turns a lot of people off as it seems complicated, but like many things, it can be as simple or as complicated as you’d like it to be. If you’re looking for a more simple approach that gets the job done but isn’t overly complicated, then head to the short version.

Pruning Process

There is a process to pruning that helps make it less overwhelming, and I strongly encourage following it to not only decrease your stress levels when this is new to you, but also to ensure you accomplish what you set out to do. Answer the following questions:

- Why are you pruning your fruit tree?

- What does that require?

By answering these questions you can determine what you need to do. If you only want to prune your tree to ensure its health and not increase its yield, then you would only need to remove crossing branches, dead branches, and possibly thin out the canopy, not prune the tree back by shortening all of the branches. The following are reasons to prune your fruit tree:

- Increasing yields

- Maintaining a smaller harvestable tree

- Control direction of future growth

- Raising the canopy to allow passage underneath

- Form stronger branches that can withstand heavy crops

- Remove dead and diseased branches

- To prevent future pests and diseases.

Types of Pruning Cuts Required: Reduction Cuts and Thinning Cuts

Pruning to increase yields is the main reason most people want to prune their fruit trees regularly. The types of cuts, when to make them, and which wood to prune varies by the type of fruit tree you’re pruning.

Apple and Pear: Flower bud formation begins in summer and occurs on spurs or branches that are 2 years old or older. Leaving at least some of the current years growth is recommended each year to slowly replace older mature growth with new fruit bearing wood. However, pruning a significant amount of the current years growth manages the tree to produce fruit over vegetative growth. This is not true of tip bearing varieties. You would want to leave some long branches to allow fruit to produce at the tip the following year. To see if your variety is tip bearing, see the link below:

http://www.royaloakfarmorchard.com/pdf/Apple_Fruiting.pdf

Peach: Flower bud formation begins in midsummer and has a tendency to bear heavily every other year (also known as biennial bearing). Peaches are unique from other stone fruit because they bear fruit only on one year old wood. This requires careful pruning to remove enough old wood to provide room for new growth while not removing more than half of the current new growth. They also do not form spurs, but instead have large lateral flower buds that are noticeable different from the usual leaf bud that alternates all the way up the branch.

Plum and Apricot: Flower bud formation begins late summer and both produce fruit on lateral buds. Fruiting occurs on the current seasons growth, and 2 year and older stubby spurs. Plums can produce 1-3 flowers at each flower bud while apricots produce only 1 per bud. While pruning, maintain fruiting spurs to ensure a good yield each year.

Sweet Cherry: Flower bud formation begins in summer and occurs on 2 year old and older wood. Each flower bud usually has about 3 flowers that emerge in spring. Cherries have pronounced apical dominance which requires regular pruning to keep the tree open and harvestable. This can also be accomplished by bending branches down.

Types of Pruning Cuts Required: Reduction Cuts, Thinning Cuts, and sometimes Heading Cuts.

Both thinning and reduction cuts are used to maintain a small tree. This can include heading cuts when long thin branches need to cut back, but there are no desirable side branches to cut back to. The branches can then set fruit buds for the following year. This prevents a situation where there are massive cut backs in the winter which removes all or most of the fruiting wood for the following season.

Time of Year: Summer time, ideally after harvest if possible.

Types of Pruning Cuts Required: Reduction Cuts and Heading Cuts.

Reduction cuts are used when a branch with a desirable direction of growth exists, and the branch is then cut back to that branch. If this branch does not exist, a heading cut is used to cut back to a specific bud that will ideally push a branch and be used as the new leader in that direction. You can control this by locating where the bud emerges on the branch and that will be the direction the new leader grows.

Time of Year: Small amounts of pruning during the year are acceptable all year, but if you’re planning on pruning more than 10-15% of the foliage on the tree then this should wait until midsummer, or winter.

Types of Pruning Cuts Required: Reduction Cuts and Heading Cuts.

While this is not typically a goal of fruit tree owners, this can be a reason for pruning. If so, you’d be using reduction cuts and ideally would be removing thick lower branches before they become too large. Take care if pruning any major side branches that are over 2″ in diameter. This can result in suckering that needs to be regularly managed throughout the following season.

Time of Year: These cuts should be done in the winter ideally, but doing it midsummer is also an option as well if you’re worried about the potential of suckering and waterspout branches emerging from a large cut.

Types of Pruning Cuts Required: Reduction Cuts and Heading Cuts.

This is necessary on peach, nectarine, and apple trees to maintain a branch strong enough to handle winds (and it other places snow) without losing large structural branches due to fruit weight.

Time of Year: This can be done both in winter and midsummer

Types of Pruning Cuts Required: Thinning Cuts and the occasional Reduction and Heading Cuts.

Time of Year: These branches can be removed at any time of the year as it helps to maintain the health of the tree and waiting for an ideal time might cause even more damage and further the disease or pest problem.

Types of Pruning Cuts Required: Thinning Cuts

Thinning out the crown of fruit trees allows airflow that can decrease ideal conditions for certain pests and diseases. Thinning out plums is a regular necessity as they tend to grow many branches close together.

Time of Year: Thinning cuts can be done in the winter. This is also much easier than doing so in leaf because you can see the branch structure clearly.

Types of Pruning Cuts

To see images and examples of the following pruning types click the button below.

Reduction Cuts

This type of cut is made to control the length of a branch by cutting it back to a smaller side branch. This is also used to control thickness and taper in the branches to ensure strength. These are important cuts to make on peach, nectarine, and apple trees as their fruit can cause breakage of even large branches. These cuts are also vital to cherries to prevent them from growing completely vertical. These cuts also control the direction of future growth as you cut back to a branch that will “take over” as the future leader for that particular branch.

Reduction cuts are frequently called heading cuts, but the main difference is defined by the leftover branch that will become the leader. If it is less than 1/3 of the diameter of the cut branch, then it is a heading cut. Reduction cuts are preferable to heading cuts as it makes for a more natural tapers to a new leader and reduces the chances of excessive branching emerging from the cut site.

Heading Cuts

Heading cuts are used to remove a growing tip in order to create more dense growth at the pruning site or to direct future growth. These cuts are rarely desired on shade and ornamental trees.

Thinning Cuts

Thinning cuts are made to “thin out” the amount of branches in the tree canopy. These cuts are made by pruning the branch off where it emerged from the larger branch or trunk. Plums are a great example of a fruit tree that needs regular thinning. Thinning allows the canopy to let air pass through which can prevent pests and diseases and allows sunlight to penetrate to all areas of the tree which aids in fruit ripening and production. These are typically the cuts made to remove branches that are crossing or rubbing against each other which can open the tree up to pests and diseases.

No-Pruning Method

While there are advocates of no-pruning methods for fruit trees, this does not mean just leaving them to grow. This requires additional techniques to keep the tree in check such as bud removal to control shading out of branches, sacrificing higher fruit to birds or for feed for your animals, and directional “pruning” through bud removal to direct the branches where you want them. While more popular amongst permaculturists, this is not the “lazy man’s” pruning method that requires no work.

To learn more about no-pruning methods you can refer to no-pruning pioneers Josef Holzer and Masanobu Fukuoka.

The Short Version

Are you overwhelmed? Here’s the simple version of everything above:

To follow the easy method for pruning fruit trees make sure to prune the following: suckers, downward growing branches, crossing branches, and any dead or diseased branches. These basic “rules” help to ensure health, and avoid potential problems. These basic pruning cuts can be made nearly at any time if it is only a few cuts, such as removing 3 smaller diameter crossing branches that have emerged. Any large cuts should be either made in June, or in the winter, and should be made just above a branch that can take over the future growth. Prune in June to cut the tree back to a manageable size while not removing all of the new growth, and in winter to control the shape and branch structure (usually a lot less pruning in the winter).

How to successfully grow productive fruit trees

Pruning During the Dormant and Summer Seasons

Pruning during the Summer can go against the common wisdom to prune while the tree is dormant, but summer pruning serves a different purpose. Summer pruning is used to control the height and size of the tree regardless of the rootstock. Doing this during the summer allows the tree to still form and produce flower buds for the upcoming year that would otherwise be severely limited by a severe cutback in the dormant seasons (winter). Peaches and Nectarines need to be pruned in June to prevent pruning off future flower buds that can set in July.

Dormant season pruning can be used when less severe cutbacks are needed/desired, to clean up your summer pruning, and for normal maintenance pruning.

Watering Your Trees Enough

Fruit trees are not meant to be a drought tolerant option, but instead are a fruit producing tree that needs to maintain optimal health to persist as a viable and productive tree. This requires regular water throughout the year and not only during hot and dry spells. This is especially relevant to our Mojave Desert dwellers.

Thinning Fruit Trees

Thinning fruit involves removing a portion of the fruit early in the year. This helps in many ways by removing weight on branches, directing growth to less fruit which makes them larger, and ensuring a consistent yield year after year instead of a heavy crop every 2 or 3 years. This is especially important for apples than are prone to produce heavy crops every 2 years.

Thinning should be done as soon as possible after fruit formation.

Mulching Your Fruit Trees

Mulch your trees. Just do it. It will do so much good for your tree that I’ve documented elsewhere. Especially because fruit production requires optimal health for good yields, mulching will go a long way to help with moisture retention and ultimate health. Ideally any organic products that are not dyed or artificial are recommended, with arborist woodchips being the ideal mulch.

Know Your Pests and Diseases

Knowing the potential problems that each of your trees is prone to will go a long way for being able to avoid and identify problems early on. Knowing this information also dictates the way you care for your tree. An example of this would be knowing that apples and other prunus species are susceptible to fireblight. Keeping an eye out for blackened branches and avoiding irrigation during flowering can help keep your trees healthy and control the potential for fireblight.

Understand Your Rootstocks

Rootstocks are often overlooked when it comes to choosing a fruit tree, but it is very important to know what it is and what care it requires. Dave Wilson Nursery, one of the largest growers of deciduous fruit, nut and shade trees in the United States, suggests “While dwarfing rootstocks have important advantages, rootstocks should be selected primarily for adaptability to the soil and climate of the planting site.” Without proper knowledge, one could easily purchase a fruit tree with a rootstock that is bound to fail in their particular soil or incorrectly care for a rootstock that causes health issues and slow decline in the tree. It is also important to state, that while many people desire dwarf fruit trees, you can buy a semi-dwarf, or even a standard sized tree, and keep it pruned at a height low enough to easily harvest it as you would with a dwarfed rootstock.

“How do you know what rootstock you have?” you may ask. I’d love to provide you with an answer to this just by looking at a photo, but the answer is that you need to look at the tag that was on the tree and see what the listed rootstock is. If you lost the tag, didn’t have one to begin with, or the nursery you purchased it from can’t tell you, you’re mostly out of luck. You’d then look at the different options and try to care for it in a way that accommodates all of the potential rootstock choices (which isn’t always possible). An example would be if you click on Apple below in the rootstock options. If you didn’t know which rootstock it was, you could be sure to keep the tree watered, as all can handle wet soils and M-27 can’t handle drought, and to stake the tree incase the rootstock happened to be a M-7 or M-27 rootstock.

I have to add, these are the common rootstocks I order from Dave Wilson Nursery, but they are not near a complete list of possible rootstocks for each variety, so there is a chance you have a different rootstock than the ones I’ve listed below.

Nemaguard

- Standard – Height of 15-25′ if unpruned

- Soil Tolerance – Excellent rootstock for well draining (sandy) soils. In slow draining soils plant on a mound or berm.

- Pests and Diseases – Resistant to root-knot nematodes

Marianna 26-24

- Standard – Height of 15-20′ if unpruned

- Soil Tolerance – Tolerant of wet soils and has a shallow root system.

- Pests and Diseases – Resistance to root-knot nematodes and oak-root fungus.

Lovell

- Standard – Height of 15-25′ if unpruned

- Soil Tolerance – Tolerant of wet soils, but is susceptible to root-knot nematodes in sandy soils.

- Pests and Diseases – Susceptible to root-knot nematodes in sandy soils

Domestic Apple Seedling

- Standard – Height of 18-30′ if unpruned

- Soil Tolerance – Tolerant of wet, dry, and poor soils. Deeply rooted

- Pests and Diseases – Resistance to woolly apple aphids and collar rot.

M-111

- Standard – Height of 15-25′ if unpruned

- Soil Tolerance – Tolerant of wet, dry, and poor soils

- Pests and Diseases – Resistance to woolly apple aphids and collar rot.

M-7

- Semi-Dwarf – Height of 12-20′ if unpruned

- Soil Tolerance – Prone to lean in shallow or rocky soils.

- Pests and Diseases – Resistance to fire blight, powdery mildew, and collar rot.

M-27

- Dwarf – Height of 6-8′ if unpruned

- Soil Tolerance – Not tolerant of drought, needs constant moisture. Needs staking due to small, shallow root system.

- Pests and Diseases – Resistance and susceptibility to pest and diseases are not well known.

Citation

- Semi-dwarf – Peach and Nectarine can reach a height of up to 8-14′ and Apricot and Plum to 12-18′ if unpruned

- Soil Tolerance – Tolerant of wet soil, but not tolerant of drought. Drought will cause early dormancy which can lead to a tree’s slow decline

- Pests and Diseases – Resistant to root-knot nematodes

Nemaguard

- Standard – Height of 15-25′ if unpruned

- Soil Tolerance – Excellent rootstock for well draining (sandy) soils. In slow draining soils plant on a mound or berm.

- Pests and Diseases – Resistant to root-knot nematodes

Myro 29C

- Standard – Height of 15-25′ if unpruned

- Soil Tolerance – Tolerant of wet soils and has a shallow, but vigorous root system.

- Pests and Diseases – Immune to root-knot nematodes and resistant to oak-root fungus.

Marianna 26-24

- Standard – Height of 15-20′ if unpruned

- Soil Tolerance – Tolerant of wet soils and has a shallow root system.

- Pests and Diseases – Resistance to root-knot nematodes and oak-root fungus.

Mazzard

- Standard – Height of 30-40′ (likely up to 25′ in the high desert) if unpruned

- Soil Tolerance – Tolerant of wet soils but still requires good drainage. and has a shallow, but vigorous root system.

- Pests and Diseases – Resistance to root-knot nematodes and oak-root fungus.

Mahaleb

- Semi-Standard – Height of 25-35′ if unpruned

- Soil Tolerance – Not tolerant of wet soils. Very cold hardy.

- Pests and Diseases – Resistance to crown gall, bacterial canker, and some nematodes.

Citation

- Semi-dwarf – Peach and Nectarine can reach a height of up to 8-14′ and Apricot and Plum to 12-18′ if unpruned

- Soil Tolerance – Tolerant of wet soil, but not tolerant of drought. Drought will cause early dormancy which can lead to a tree’s slow decline

- Pests and Diseases – Resistant to root-knot nematodes

Nemaguard

- Standard – Height of 15-25′ if unpruned

- Soil Tolerance – Excellent rootstock for well draining (sandy) soils. In slow draining soils plant on a mound or berm.

- Pests and Diseases – Resistant to root-knot nematodes

Lovell

- Standard – Height of 15-25′ if unpruned

- Soil Tolerance – Tolerant of wet soils, but is susceptible to root-knot nematodes in sandy soils.

- Pests and Diseases – Susceptible to root-knot nematodes in sandy soils

Citation

- Semi-dwarf – Peach and Nectarine can reach a height of up to 8-14′ and Apricot and Plum to 12-18′ if unpruned

- Soil Tolerance – Tolerant of wet soil, but not tolerant of drought. Drought will cause early dormancy which can lead to a tree’s slow decline

- Pests and Diseases – Resistant to root-knot nematodes

Nemaguard

- Standard – Height of 15-25′ if unpruned

- Soil Tolerance – Excellent rootstock for well draining (sandy) soils. In slow draining soils plant on a mound or berm.

- Pests and Diseases – Resistant to root-knot nematodes

Lovell

- Standard – Height of 15-25′ if unpruned

- Soil Tolerance – Tolerant of wet soils, but is susceptible to root-knot nematodes in sandy soils.

- Pests and Diseases – Susceptible to root-knot nematodes in sandy soils

OHxF333

- Standard – Height of 12-18′ if unpruned

- Soil Tolerance – Widely adapted to varying soils.

- Pests and Diseases – Disease resistant

Calleryana

- Standard – Height of 15-20′ if unpruned

- Soil Tolerance – Sandy or heavy soils

- Pests and Diseases – Great rootstocks for warm winter and hot summers.

Standard Pear

- Standard – Height of 15-25′ if unpruned

- Soil Tolerance – Moderately tolerant of wet soils.

- Pests and Diseases – Resistance to oak-root fungus and pear decline.

Citation

- Semi-dwarf – Peach and Nectarine can reach a height of up to 8-14′ and Apricot and Plum to 12-18′ if unpruned

- Soil Tolerance – Tolerant of wet soil, but not tolerant of drought. Drought will cause early dormancy which can lead to a tree’s slow decline

- Pests and Diseases – Resistant to root-knot nematodes

Nemaguard

- Standard – Height of 15-25′ if unpruned

- Soil Tolerance – Excellent rootstock for well draining (sandy) soils. In slow draining soils plant on a mound or berm.

- Pests and Diseases – Resistant to root-knot nematodes

Myro 29C

- Standard – Height of 15-25′ if unpruned

- Soil Tolerance – Tolerant of wet soils and has a shallow, but vigorous root system.

- Pests and Diseases – Immune to root-knot nematodes and resistant to oak-root fungus.