What Is Fire Blight?

Fire blight (Erwinia amylovora) is a destructive pathogen that is widespread throughout many regions. It is highly contagious and, if left unchecked, can destroy entire orchards in a full growing season.

Symptoms and Identification of Fire Blight

Fire blight affects plants of the Rosaceae family. These include (but are not limited to) the following common garden and landscaping plants: Prunus (cherry, apricot, almond, nectarine, peach, plum), Malus (apple, crab apple), pyracantha, flowering quince, hawthorn, loquat, flowering pear, quince, cherry laurel, rose, and spirea.

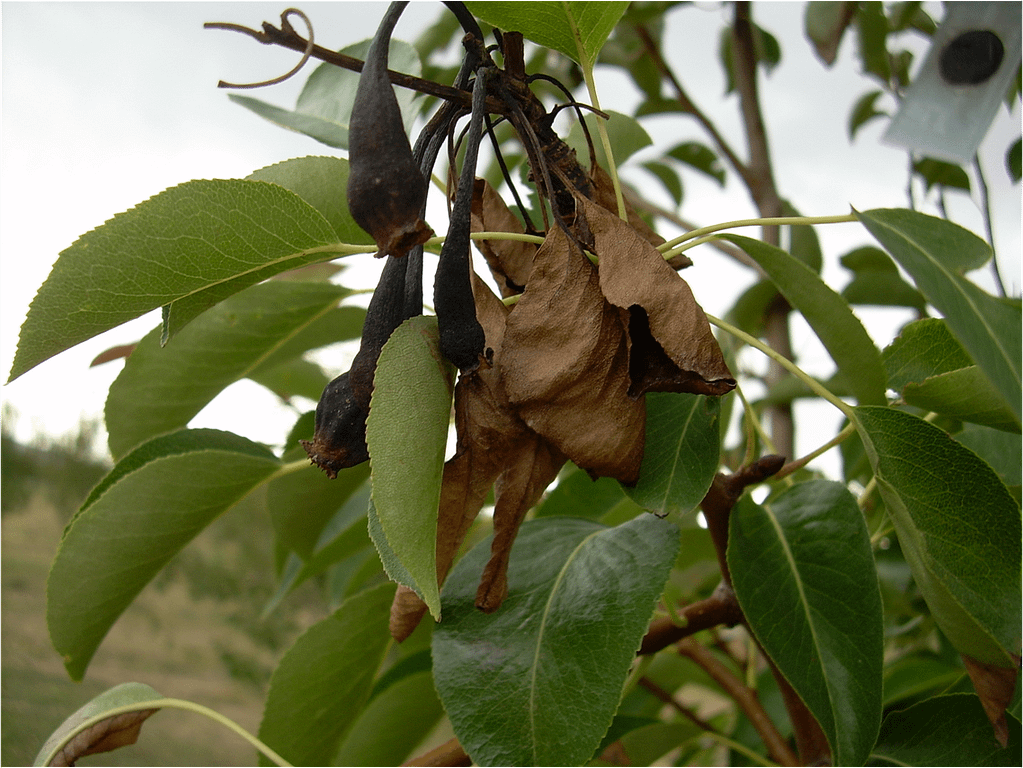

Symptoms of fire blight include the following:

- Branches that appear burned

- Branches that are bent resembling a “shepherd’s crook”

- Leaves and fruit remain on the dead branches

- Leaves can show blackening along the midrib and veins before completely turning black

- Young branches die from the tip of the branch

- Blighted twigs will have bark at the base that becomes water soaked and then dark, with a sunken, dry look to them

- Blossoms appear grayish green and are water soaked

- High humidity can cause ooze to form on water-soaked tissue. This ooze starts white and becomes amber as it ages.

- Rootstock can become infected as well and it generally appears near the graft union. This can be confused with Phytophthora collar rot. Malling 26 and 9 are rootstocks highly susceptible to fire blight.

For images of plants with fire blight scroll to the bottom for help in identifying if it is affecting your plant. If you have photos you’d like to add to the photos below you can send them to [email protected].

Life Cycle

Fire blight enters a tree through natural openings such as flowers, and through wounds on the tree in the Spring. It can also enter a tree through bees and other insects that are attracted to ooze that forms from cankers on diseased branches. Pruning tools, rain and wind can also spread fire blight. Fire blight can overwinter on infected branches, and persist in the tree indefinitely if not dealt with.

Once it infects a plant, it will quickly move through the current season’s growth into older growth, especially if the temperature is between 70-80°F.

One place it mentions that once a plant is infected, it will harbor the pathogen indefinitely, but I haven’t seen that mentioned anywhere else.

Management of Fire Blight

Monitoring

Monitoring is of utmost importance, as the sooner you catch it the less of your tree it will infect. During the high susceptibility time (Early Spring when blossoms are out and when secondary blossoms are out) you need to be regularly checking to ensure your tree isn’t infected. After that period, intense vigilance isn’t necessary.

Cultural Control

Not watering during bloom helps to keep the ideal environment for fire blight at bay. In extremely wet Springs, one can remove flowers by hand in order to prevent potential infection.

Prune out infected branches whenever they are noticed. I’ve seen recommendations to prune 8″ below the infected area, and recommendations to prune at least 12-18″ below the visible infection in older trees with a slower growth rate and 2-4′ below the infection in young trees. After diving through the information overload of various universities, I’d suggest pruning as far back as possible. The visible symptoms do nothing to show how far the pathogen has gone in the vascular system of the tree, so if there is 4′ of branching to cut back, I’d cut it all off. If you have to cut off 70% of the tree to reach 4′, then you can be a bit less aggressive, but you always run the risk of reinfection. See chemical control for ways to help prevent reinfection. Sterilizing of pruners has recently shown to be ineffective at controlling the pathogen, and painting the branch with Actiguard helps to keep the pathogen from coming back.

Avoid excessive nitrogen fertilization as fresh new succulent growth has a higher susceptibility to infection. Succulent growth can also be a product of severe pruning or pruning right before bud break. To avoid these situations when fire blight is a concern or past infection has been present, you can prune after leaves have set in Spring and the tree has less resources, or prune in Summer dormancy (regular temperatures above 95°F) when growth is slowed.

Thinning out the canopy of susceptible trees helps to avoid humidity and a dense, air restricted growing space within the tree. This discourages fire blight as it eliminates the ideal environment for fire blight causing pathogens.

Chemical Control

I will not cover preventative chemical treatments, as the types, species, and application times vary depending on many factors and require reapplication every 3-4 days. This is typically geared towards orchard management and could take its own entire post to cover. For more information about preventative chemical treatments Washington State University has great information about them here: http://treefruit.wsu.edu/crop-protection/disease-management/fire-blight/

As for reactive treatment, Actiguard (acibenzolar-S-methyl) has been shown to provide beneficial results. In this article on Goodfruit.com, Ken Johnson, a plant pathologist at Oregon State University, gives the following recommendation for application: “Painting a 1-meter stretch on the central leader with Actiguard at 1 ounce per quart along with a silicon surfactant induces resistance in the whole tree, he said.”

In this study it was shown that painting ASM (Actiguard) on the branches after being pruned reduced the reinfection rate of fire blight up to 25%, where the reinfection rate without it was around 50%.

Toxicity

As with almost all chemicals there is an associated toxicity rating for the active ingredients of different pesticides, fungicides, herbicides, and rodenticides. Here are a few places you can learn more about their toxicity with a table of their rating and what the rating means (first is the preferred):

http://pods.dasnr.okstate.edu/docushare/dsweb/Get/Document-3591/EPP-7457web.pdf

https://extension.psu.edu/toxicity-of-pesticides